NOW we come to one of the most famous games in chess history, about which more nonsense has been written than probably any other encounter.

Lasker - Capablanca, St Petersburg Finals Round 7, is famous despite being very much short of the fireworks that mark out most celebrated games.

As the story is usually told, Capablanca was running away with the tournament and only needed to draw against Lasker to virtually guarantee first place.

Lasker, as usual, began quite slowly and, with just four rounds to go, he was trailing a full point behind Capablanca, whom he was desperately trying to catch. His last chance to fight for tournament victory was to beat the leader - Garry Kasparov, ChessBase's Mega database.

The young Cuban, who was confidently leading the tournament, needed only not to lose with Black against the current world champion in order to claim overall tournament victory - Vladimir Tukmakov in Modern Chess Preparation, New In Chess 2012.

Capablanca wanted a draw, because he was Black and because a half point would virtually clinch first prize, Réti said - Andrew Soltis in Why Lasker Matters, Batsford 2005.

What Réti actually wrote was:

In Capablanca's remarkably cautious playing in this game it is easy to see that, owing to his favourable standing in the tournament, he has determined to play only for a draw - Masters Of The Chessboard, Dover 1976 reprint of the first English edition of 1932.

There is much more along these lines on the internet, where people seem prone to confuse Capablanca's standing at the start of the finals, where he was 1.5pts ahead of Lasker from the preliminary rounds, with his position when the two met in the finals with four rounds to go.

The truth is that when Lasker played Capablanca in this famous game, they were joint-first on 11pts.

However, it is fair to say Capablanca was still favoured by many to win the tournament.

The reason has to do with the unusual format at St Petersburg.

It began in the preliminaries with 11 players, the favourites being generally acknowledged as the world champion (Lasker), the fast-rising Capablanca, and Akiba Rubinstein, arguably the strongest player never to have played for the world title.

Five players would qualify for the finals, but they were not to include Rubinstein. Instead they consisted of Capablanca (unbeaten on 8pts), Lasker and Tarrasch (6.5pts), and Alekhine and Marshall (6pts).

Whether these famous five were dubbed grandmasters by Tsar Nicholas II is extremely doubtful, but at any event they would compete in a double-round-robin, bringing forward their scores from the preliminaries.

Because there were five players in the finals, one in every round was given a no-point bye.

By the time they reached round seven, where Lasker had the white pieces against Capablanca, the latter had already had his two byes, while the world champion was due one in the following round.

This meant that after their game, Capablanca had three more games (White against Tarrasch, Black against Marshall and White against Alekhine). Lasker had just two more games (Black against Tarrasch and White against Marshall).

I am sure I will not be spoiling it for anyone by stating that Lasker beat Capablanca. This gave him 12pts to the Cuban's 11pts.

The next day, in round eight, while Lasker sat it out, Capablanca went down to Tarrasch, remaining a point behind Lasker, and now having played an equal number of games.

But the drama was not over. In round nine, Lasker was held to a draw by Tarrasch, while Capablanca beat Marshall, setting up a dramatic last round.

Capablanca duly beat Alekhine to reach 13pts, but Lasker also despatched Marshall, winning the tournament with 13.5pts.

Here is the game about which so much has been written.

Lasker - Capablanca

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Bxc6

Kasparov: "(!) A very surprising choice. The Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez was a dangerous weapon in Lasker's hands. But nobody in the audience and amongst the participants believed that this quiet opening would work against Capablanca, whose excellent technique was already widely recognised. With the charming self-confidence of youth, José Raoul unfortunately shared this misconception and did not recognise Lasker's real intentions."

Soltis: "Tarrasch said that when the game was adjourned for a meal break, he asked Lasker why he chose 4.Bxc6. Lasker replied that he had studied Tarrasch's new idea in the Open Defence and couldn't find an improvement for White. Lasker feared that Capablanca would use the same opening. But this sounds like another Lasker smokescreen. Capablanca never played the Open Defence in his career, and Lasker often played the Exchange Variation without a special reason."

4...dxc6 5.d4 exd4 6.Qxd4 Qxd4 7.Nxd4

Kasparov: "Now even the queens are off the board. Is this the way to play for a win in the decisive game?"

Lasker in Lasker's Manual Of Chess

(Dover 1960 reprint of the original 1947 David McKay Company edition): "Black must not refuse this simplification, otherwise he loses too much space."

7...Bd6

Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals (Bell 1973 reset reprint of original 1921 edition): "Black's idea is to castle on the kingside. His reason is that the king ought to remain on the weaker side to oppose later the advance of White's pawns."

Réti: "The bishop is very well-posted here. That is, if White succeeds in exchanging it, in order to deprive the second player of the weapon furnished by the two bishops, then, after the pawn recaptures on d6, Black's pawn-position will also be improved."

8.Nc3 Ne7 9.0-0

Reinfeld & Fine in Lasker's Greatest Games 1889-1914 (Dover 1965 reprint of the original 1935 The Black Knight Press edition entitled Dr. Lasker's Chess Career, Part I: 1889-1914): "Unusual but good: the king is to support the advance of the kingside pawns."

I played the more popular 9.Be3, and later castled queenside, in a win over a junior rated 1744/150 at Hastings 2019-20, but as I noted in part three of this series, Lasker generally kept his king on the kingside in 5.d4 lines of the Spanish Exchange, although often preferring long-castling if he had played 5.Nc3.

9...0-0

Reinfeld & Fine: "Also unusual, but this time less good. Black should castle queenside in order to guard his weak pawns."

Réti: "In a later game, Schlechter played at this point against [me] the much better move ...Bd7, combined with queenside castling [Vienna Trebitsch Memorial 1914, 0-1 39 moves]."

The text is the most-popular move, from a small sample, in ChessBase's Mega20, and was played four years ago by 2509-rated Nikita Petrov in a draw against Yuri Korsunsky (2411).

10.f4

Capablanca: "This move I considered weak at the time, and I do still. It leaves the e pawn weak, unless it advances to e5, and it also makes possible for Black to pin the knight by ...Bc5."

Reinfeld & Fine: "Having the majority of pawns on the kingside, Lasker immediately sets out to utilise this advantage."

10...Re8

Capablanca: "Best. It threatens ...Bc5, Be3 Nd5. It also prevents Be3 because of ...Nd5 or ...Nf5."

Reinfeld & Fine: "Superior to the text was 10...f5 11.e5 Bc5 12.Be3 Bxd4! 13.Bxd4 b6 [Korunsky - Petrov, EU-Cup Novi Sad 2016, saw 13...Rfd8 14.Bf2 Ng6, with Black later successfully blockading White's passer] 14.Rad1 c5 15.Be3 Be6, and in view of the bishops of opposite colour and Black's initiative on the queenside, the position is about even."

Soltis gives the text an exclamation mark, stating that it "threatens to seize an edge with 11...Bc5 12.Be3 Nd5!"

Réti: "A more vigorous move would be ...Bc5, which Lasker prevents with his following move, which is excellent."

Kasparov: "Later Dr Tarrasch suggested a better line: 10...f5 11.e5 Bc5 12.Be3 Bxd4 13.Bxd4 b6, and despite White's strong passed pawn, Black has enough defensive resources. So strong was the impression of Lasker's original plan that the commentators tried to improve Black's play at the earliest possible stage! But Capablanca was right in his assessment: Black had little to worry about."

For what it is worth, Stockfish10 and Komodo10 agree with Capablanca and Soltis.

11.Nb3 f6

Lasker (commenting generally on ...f6 in the Spanish Exchange rather than on this exact position): "The move ...f6, ordinarily weak becomes very effective after the exchange of the hostile king's bishop. This observation is due to Steinitz. Bernstein has applied it happily in recommending against 5.Nc3 the defence 5...f6 in this Exchange Variation."

Réti: "An absolutely unnecessary defensive move, for White's e5 would be of advantage only to Black, since he would have the points d5 and f5 free for his pieces."

Soltis: "Before this game, the move ...f6 was considered good for Black in the Exchange Variation, 'even necessary' said [Russian master Samuil] Vainshtein.

After the game, annotators dismissed ...f6 as questionable because 'it makes [the move] f5 stronger'. We [have] got so much smarter over the years that when ...f6 is played, it's taken for granted that f5 will be strong."

Reinfeld & Fine: "Preventing e5 but weakening e6. Preferable was 11...Be6 and if 12.e5 [then] 12...Bb4 with good chances."

Capablanca: "Preparatory to ...b6, followed by ...c5 and ...Bb7 in conjunction with ...Ng6, which would put White in great difficulties to meet the combined attack against the two centre pawns."

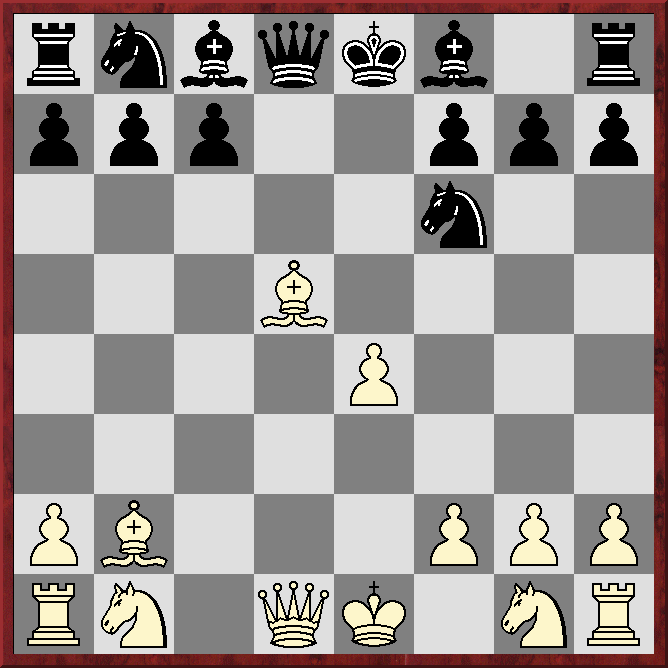

|

| White to make his famous 12th move |

*****

*****

*****

*****

*****

12.f5!?

Kasparov awards this an exclamation mark, stating: "Under the classical rules of the Steinitz positional school this move has to be damned. White gets a weak pawn on e4, Black a stronghold on e5, with a devaluation of White's pawn-advantage on the kingside -- too many negative points for just one move. But Lasker's eagle eye had seen much further."

Capablanca: "It has been wrongly claimed that this wins the game, but I would like nothing better than to have such a position again. It required several mistakes on my part finally to obtain a lost position."

Tukmakov awards an exclamation mark, with the laconic note: "12.Be3 Nd5!"

Reinfeld & Fine also give an exclamation mark, stating: "A surprising and courageous move which gives White a definite advantage. The move creates a hole for Black's pieces at e5, but it helps White in three ways: 1) it fixes Black's f pawn, enabling White to undertake a kingside attack with g4-g5; 2) it contains Black's queen's bishop; 3) it will later enable White to plant a knight at e6. The fact that Lasker was able to carry out every one of these objectives, shows that Capablanca did not properly grasp the essentials of the position."

Soltis: "Tarrasch had ridiculed f5 when it occurred in a similar position … but Tarrasch's knee-jerk classicism had been proven wrong when Lasker won [against Salwe five years earlier at St Petersburg 1909] and the f5 idea had worked reasonably well in other previous games."

Réti: "A surprising move. On closer examination, however, it is perceived that … apparent disadvantages go hand in hand with less apparent but actually more important advantages."

12...b6

Kasparov: "12...Bd7 13.Bf4 Rad8 was recommended by stern post-mortem analysts. But obviously the bishop is better placed on b7, where it attacks the pawn on e4."

Reinfeld & Fine: "A wiser continuation was 12...Bd7 and if 13.Bf4 [then] 13...Bxf4 14.Rxf4 Rad8 15.Rd1 Bc8 and White will find it difficult to press home his advantage."

Soltis: "From this point on the annotators looked for a way to save Black's position - a remarkable admission of the strength of 12.f5."

Réti: "Because Capablanca hits on the unfortunate idea of withdrawing his queen's bishop from the defence of the point e6, that point becomes much weaker than e5 is for White. The simplest alternative is probably the development ...Bd7, combined with ...Rad8."

Tukmakov gives 12...Bd7 13.Bf4 Rad8 without comment.

13.Bf4 Bb7

Kasparov gives this move a question mark, commenting: "Now a serious mistake! In general Black should be happy to undouble his c-pawns, but here the pawn on d6 will become a permanent weakness."

Capablanca: "Played against my better judgment. The right move of course was 13...Bxf4."

Soltis also awards a question mark, saying Capablanca's suggestion has been "analysed well into a minor-piece ending."

Réti says Black was "absolutely forced to exchange."

14.Bxd6

Reinfeld & Fine: "Good: now Black has a new weakness at d6."

Soltis gives the move an exclamation mark, stating: "White makes the d pawn the board's only real target."

14...cxd6 15.Nd4

Capablanca: "It is a curious but true fact that I did not see this move when I played 13...Bb7."

15...Rad8

Capablanca: "The game is yet far from lost, as against the entry of the knight, Black can later on play ...c5, followed by ...d5."

Kasparov gives the move a question mark, stating: "Capablanca doesn't take White's plan seriously. The knight on e6 will be a bone in the throat. So 15...Bc8 was obligatory. Maybe the Cuban was too proud to recognise his mistake so soon."

Reinfeld & Fine also award a question mark: "After this he will never be able to drive White's knight from e6."

Soltis says White's advantage is not great after 15...Bc8 "but it is enough to play for a win."

16.Ne6 Rd7 17.Rad1

Capablanca: "I now was on the point of playing ...c5, to be followed by ...d5, which I thought would give me a draw, but suddenly I became ambitious and thought I could play 17...Nc8 and later on sacrifice the exchange for the knight at e6, winning a pawn for it, and leaving White's e pawn still weaker."

Soltis says White would be much better after 17...c5 18.Nd5 Bxd5 19.exd5 b5 20.g4! with a kingside attack.

Reinfeld & Fine say 17...c5 18.Bf2, followed by Rfd2, "would practically stalemate all of Black's pieces."

17...Nc8 18.Rf2 b5

Reinfeld & Fine: "In order to obtain some more room. But the move eventually leads to the opening of the a file, which can only result in White's favour because of his superior mobility. Black's best chance was to give up the exchange."

Unfortunately, the immediate ...Rxe6?, if this is what they meant, fails to the engines' 19.fxe6 Re7 20.e5!, when 20...dxe5? leads to mate after 21.Rd8+ while 20...fxe5 21.Rdf1 Re8 22.Ne4 is not much better, eg 22...d5 23.e7! Nxe7 24.Nd6. That leaves 20...Rxe6, which is met by 21.exd6 Nxd6 22.Rfd2 Nf7 23.Rd7 with a large advantage.

19.Rdf2 Rde7

The engines reckon 19...b4 gives more hope, but much prefer White after 20.Ne2.

20.b4

Reinfeld & Fine: "Stops ...c5 or ...b4."

20...Kf7 21.a3 Ba8

Capablanca: "Had I played ...Rxe6, fxe6 Rxe6, as I intended to do when I went back with the knight to c8, I doubt very much if White would have been able to win the game. At least it would have been extremely difficult."

Kasparov says Capablanca's line "would have given him the best fighting-chances."

Soltis says Black, after the exchange sacrifice, "can establish a semi-fortress, with his king at e7 and knight at c4." He suggest best play runs 23.Rd4 c5! 24.bxc5 dxc5 25.Rd7+ Re7 "followed by ...Nb6." He concludes: "Black is not losing." The engines continue 26.Rd8 Nb6, when Stockfish10 reckons 27.Nd5 Bxd5 28.exd5 Rd7 29.Rb8 Nc4 30.Rc8 is winning, but Komodo10 'only' gives White the upper hand.

22.Kf2 Ra7 23.g4

Réti: "We recognise once more the type of game in which the advantage of controlling more territory is turned to account."

23...h6 24.Rd3 a5 25.h4 axb4 26.axb4 Rae7

Capablanca: "Black, with a bad game, flounders around for a move. It would have been better to play ...Ra3 to keep the open file, and at the same time to threaten to come out with the knight at b6 and c4."

27.Kf3 Rg8 28.Kf4 g6 29.Rg3 g5+

Kasparov: "The last move to be criticised by the annotators. But it's too late for good advice."

30.Kf3 Nb6 31.hxg5 hxg5 32.Rh3!

Kasparov: "32.Rxd6 would have given Black some extra breathing time."

32...Rd7 33.Kg3 Ke8 34.Rdh1 Bb7 35.e5! dxe5 36.Ne4 Nd5 37.N6c5 Bc8

Or, for example, 37...Rdg7 38.Nxb7 Rxb7 39.Nd6+.

The game finished:

38.Nxd7 Bxd7 39.Rh7 Rf8 40.Ra1 Kd8 41.Ra8+ Bc8 42.Nc5 1-0