Rivière was strong enough to win matches against Thomas Barnes and Johann Löwenthal, and only lost to Mikhail Chigorin by the narrow margin of +4=1-5.

Rivière - Morphy

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.b4 Bxb4 5.c3 Bc5!?

After scoring six out of six with 5...Ba5, Morphy switches to a line that today is less popular even than 5...Be7, and much less popular than 5...Ba5.

Botterill* says of ...Bc5: "This old-fashioned defensive line, so far as I can see, has no particular advantage over 5...Ba5, whereas there is the significant disadvantage that after d4 Black is obliged to play …exd4, ceding control and allowing White to rid himself of a potentially weak pawn on c3."

Harding says that only 5...Ba5 "seriously threatens to seize the initiative." But he adds: "With both moves there are numerous offshoots for both White and Black, including some little-known byways which, though not essential for White to know, give him added chances of advantage."

Kaufman only covers 5...Ba5.

Bologan covers ...Bc5 extensively, writing: "With this line we are entering a time machine and going back to the romantic 19th century."

For what it is worth, White scores a significantly better percentage score against ...Bc5 than against ...Ba5 or ...Be7 in ChessBase's 2019 Mega database.

6.0-0

Botterill and Harding only mention the more common 6.d4, while Bologan points out that 6.0-0 d6 7.d4 returns to the 6.d4 mainline after 7...exd4, which is indeed what happens in this game.

6...d6 7.d4 exd4

7...Bb6 is a little-played alternative that is slightly preferred by the analysis engines Stockfish10 and Komodo10.

8.cxd4 Bb6

|

| Botterill: "Thus we arrive at the Normal Position - so called because for much of the 19th century it was what you could expect to get when playing the Evans Gambit." |

*****

*****

*****

*****

9.d5

Botterill: "This was how [Adolf] Anderssen used to play it, but I think it is a positional mistake that really deserves a question mark." However, he does not actually give it one, and the move has remained reasonably popular, although eclipsed by 9.Nc3.

Harding only covers 9.Nc3, "the move always chosen by Morphy and Chigorin."

Bologan calls 9.d5 "very important because in [other] lines every now and then White can push d4-d5, creating the pawn-structure characteristic for this line."

9...Na5

Botterill: "Black set[s] to work on exploiting his queenside majority with ...c5 and ...b5. Admittedly the position is double-edged, and White has his practical chances (swindles), but with best play Black ought to prevail."

10.Bd3 Ne7 11.Bb2 0-0 12.Nbd2

Botterill only covers the much more popular 12.Nc3.

12...Ng6

Bologan says this is also the move to play if White tries 12.Nd4.

13.Nd4?!

Probably a mistake, as we will see. The engines give 13.Re1, with full compensation for the pawn, according to Stockfish 10, but Komodo10 likes Black.

13...Qf6 14.N2f3 Bg4?!

Bologan gives 14...c5!, which was played by Robert Byrne against an unrated at the 1989 World Open in Philadelphia. After 15.dxc6 Nxc6 16.Bb5 (16.Nxc6 Qxb2 is also good for Black) Nce5, Black had an aggressive position while still being a pawn up.

15.Qc2

White's pieces menace Black's kingside in general and his queen in particular.

15...Bxf3?!

The engines prefer an immediate …Ne5.

16.Nxf3 Ne5?

16...Qd8, as suggested by the engines, is the type of retreat Morphy was not fond of making, but it, or 16...Qe7, may have been best.

17.Kh1

White gets a strong attack.

17...Qe7 18.Nxe5 dxe5 19.f4 f6 20.Qc3?

Rivière seems to have missed the full effect of Black's reply.

White wins, according to the engines, by targeting the a5 knight with 20.Qd2 or 20.Qa4.

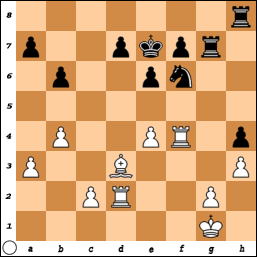

20...Bd4 21.Qxa5 Bxb2 22.Rab1 b6 23.Qd2 Bd4 24.f5 a6

White's much-inferior bishop means Black has no more worries about a kingside attack.

25.Bc4 Qd6 26.a4 Rfb8 27.Rb3 Kf8!?

Played so a later ...d6 will not come with a discovered check, but 28...Kh8 is a safer way of having the same effect.

28.Qe2 b5 29.axb5 a5?

29...axb5 30.Bxb5 Ra3 is equal. The text is a misguided attempt to create winning chances.

30.Rg3 a4 31.Qh5 h6

31...Kg8 loses to 32.Qh6.

32.Qg6 Qe7 33.d6 cxd6 34.Qh6 Qf7

The best try, but inadequate.

35.Qh8+

Winning, but even stronger was 35.Qh7 Qxc4 36.Qxg7+ Ke8 37.Qh8+ Ke7 38.Rg7+ etc.

35...Ke7 36.Rxg7 Rxh8 37.Rxf7+ Ke8 38.Rxf6

Black is two pawns down, and his d pawn is hanging, but the passed a pawn gives him hope of complicating the issue.

38...a3 39.Ba2 Rc8 40.b6 Kd7?

The b pawn is too dangerous to be left on the board.

41.b7 Rc2 42.Be6+

Good enough, but perhaps easiest was 42.Rf7+ Kc6 43.Bd5+ Kb6 44.Rh7 Rb8 45.f6 a2 46.Bxa2 Rxa2 47.f7 etc.

42...Kc7 43.Rb1?

But now the win has gone. Still good for White was 43.Rf7+ Kb8 44.f6.

43...Kb8 44.Bb3??

Any reasonable move draws, eg 44.h3 Rd8 45.Rf7 a2 46.Bxa2 Rxa2 47.f6 Rf2, with dead-eye equality, according to both engines.

44...Rb2 45.Rxb2

There is nothing better.

45...axb2 46.Ba2 Kxb7 47.Rxd6 Ra8 0-1

*I am comparing play with two specialist books: Open Gambits: Italian And Scotch Gambit play by George Botterill (Batsford 1986) and Evans Gambit And A System Vs. Two Knights' Defense by Tim Harding (Chess Digest, 1991); and with two respected repertoire books: The Chess Advantage In Black And White by Larry Kaufman (McKay Chess Library, 2004) and Bologan's Black Weapons In The Open Games: How To Play For A Win If White Avoids The Ruy Lopez by Victor Bologan (New In Chess, 2014).