SOME people believe, or at least imply, that sacrificing the exchange is a relatively modern technique.

The following game shows the idea was in circulation and practised almost 200 years ago, and was almost certainly known long before then.

It is from a series of matches played in London in 1834 between Louis-Charles de Labourdonnais and Alexander McDonnell.

Notes in italics are algebraicised from 500 Master Games Of Chess by Savielly Tartakower and Julius du Mont.

Labourdonnais - McDonnell

Match One, Game 21

Bishop's Opening

1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 Bc5 3.Qe2

A supporting move, indicated as early as 1561 by Ruy Lopez, with the ingenious threat of Bxf7+.

3...Nf6

Besides this purely developing move, the replies 3...d6 and 3...c6 are useful.

4.d3

A wise procedure. Strategy lacking in foresight would prompt 4.Bxf7+ Kxf7 5.Qc4+ d5 6.Qxc5 Nxe4, with advantage to Black. With the text move White reserves the option of developing his kingside by 4.Nf3 or 4.f4.

4...Nc6 5.c3 Ne7!?

Premature would be 5...0-0, on account of 6.Bg5, and if, impulsively, 6...h6 [then] 7.h4 etc.

The game Edmund Thorold - Miksa Weiss, British Chess Association Congress (Bradford, West Yorkshire) 1888, continued 7...d6 (7...hxg5 9.hxg5 is probably better for White, but after the text Black is really threatening to capture the white queen's bishop) 8.Bxf6 Qxf6, when the analysis engines Stockfish14.1 and Komodo12.1.1 reckon Black is better (but 1-0, 35 moves).

6.f4!?

Having consolidated his base, White now challenges the centre.

The engines strongly dislike the text, preferring 6.Nf3.

6...exf4

The engines give 6...d5!?, meeting 7.fxe5 with 7...Nxe4!?, when 8.dxe4 dxc4 9.Qxc4 runs into 9...Bxg1 10.Rxg1 Ng6, after which White is a pawn up but faces numerous threats. Better seems to be 8.Bb5+ c6 9.dxe4 Bxg1 (not 9...cxb5? 10.Qxb5+) 10.Rxg1, although the engines reckon Black has the advantage after 10...cxb5, eg 11.Qxb5+?! Bd7 12.Qxb7 0-0 13.exd5 Ng6 gives Black huge compensation for being three pawns down.

7.d4 Bb6 8.Bxf4

With a strong pawn-centre, White has satisfactorily solved the problem of the opening - but Black, without losing faith, is looking for some weakness in the enemy camp.

The engines prefer 8.e5!?

8...d6

McDonnell was famous for his aggressive play, but here he misses a chance to challenge the white centre with 8...d5!? Also interesting is winning the bishop-pair with 8...Nxe4!? - the engines reckon White's best response is 9.Bxf7+ Kxf7 10.Qxe4, albeit preferring Black after 10...d5 or 10...Re8.

9.Bd3!?

This prevents ...Nxe4 and plans to meet 9...d5 with 10.e5 at a time when Black does not have ...Ne4. However development with 9.Nd2 looks more natural, while the engines like 9.Bg5 Ng6, and then 10.Nd2.

9...Ng6 10.Be3 0-0 11.h3!?

Preventing ...Bg4 and preparing, in anticipation of castling long, a kingside attack, but the engines prefer developing with 11.Nf3 or 11.Nd2.

11...Re8

An indication of Black's idea to exert pressure on the semi-open king's file, although, for the moment, White's e pawn can be adequately defended.

12.Nd2 Qe7!?

Black's pressure continues. It is in itself an achievement for Black to have some counterplay at this stage, or at least some definite objective.

The engines are unimpressed, preferring 12...d5, meeting 13.e5 with 13...Nxe5! 14.dxe5 Rxe5 15. Nf1 (forced) Nh5, which seems a winning attack. Perhaps White should play 13.0-0-0!? dxe4 14.Bc2, when Black is a pawn up but opposite-side castling introduces a large degree of uncertainty.

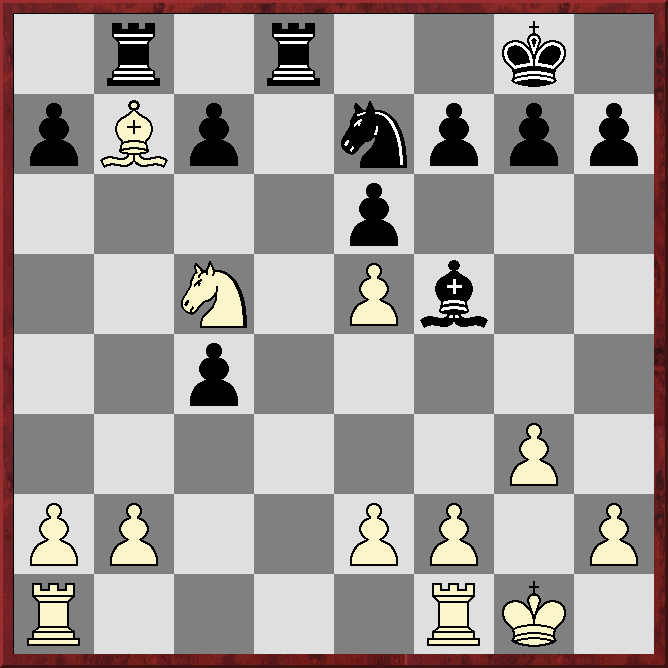

13.0-0-0

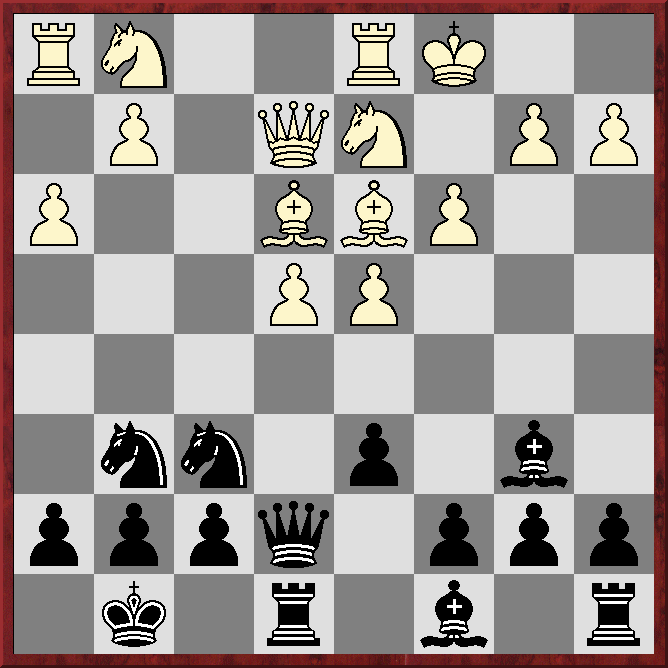

|

| How would you assess this middlegame? |

*****

*****

*****

*****

*****

White has more space in the centre and the white pieces seem better coordinated, but the pawns in front of the black king are unmoved while the white king's defences are slightly compromised. Stockfish14.1 for a long time gives Black a slight edge, but comes to agree with Komodo12.1.1 that the position is more-or-less equal.

13...c5

Undermining the hostile centre.

14.Kb1?!

A standard idea, but it costs a tempo and sometimes it is played unnecessarily, which seems to be the case here. The a2 pawn was not threatened and was unlikely to be for the foreseeable future. Probably better is developing with 14.Ngf3.

14...cxd4 15.cxd4

Although White's centre is still very strong, it has now to be self-supporting.

15...a5?!

The engines strongly dislike this. It seems Black should concentrate on attacking the white centre, for example by 15...Bd7, intending 16...Bc6.

16.Ngf3 Bd7 17.g4

A waiting policy in the centre - attack on the wing; such is White's motto.

The engines prefer supporting the centre with 17.Rhe1.

17...h6?

This creates a target for White's kingside attack, while 17...Bc6 ups the ante against the white centre.

18.Rdg1?

Too slow. White is better after 18.g5.

18...a4?!

Nor does Black remain inactive.

Consistent, but almost certainly wrong. The engines like 18...Bc6.

19.g5 hxg5 20.Bxg5 a3

Disrupting the defences of the white king seems to be Black's best chance as by now ...Bc6 is too slow in the face of 21.h4 etc.

21.b3

This comes to be Komodo12.1.1's top choice, for a while, but eventually the engines settle on 21.Nc4, although after 21...Ba7 White's best may not be 22.Nxa3 as 22...Qe6 breaks the pin on the f6 knight and so gives counterplay. However the engines' 22.h4!? look promising.

21...Bc6?!

This still seems to be too slow. Sharp and interesting is the engines' 21...d5!?, the idea being to meet 22.e5 with 22...Qb4, pinning the e pawn. Then best-play, according to the engines, runs 23.Bxf6 Qc3 24.Nf1 Bxd4 25.Nxd4 Qxd4 26.Nh2!? (26.Bg5? Rxe5) gxf6 27.Bxg6 fxg6 28.Rxg6+ Kf7 29.Rxf6+ Ke7, when White is a pawn up but the position remains sharp and unclear.

22.Rg4?!

Of course not 22.d5 Bxd5, eg 26.exd5 Qxe2 27.Bxe2 Rxe2 etc, or 23.Bxf6 Qxf6 with the sudden threat of 24...Qb2#. The necessity for the artificial manoeuvre in the text demonstrates that White's centre has only hypothetical power and mobility. It is continually exposed to attack, and there is no threat at all of a breakthrough.

The engines reckon 22.h4!? leaves White well on top, and if 22...Bxe4!? then 23.h5 Nf8 24.Nxe4 Nxe4!? 25.Bxe4 Qxe4 26.Qxe4 Rxe4 27.Bf6 wins, eg 27...Ne6 28.h6 etc.

22...Ba5?!

An eliminating manoeuvre.

In this unclear position the engines prefer breaking a pin with 22...Qe6, bring the queen's rook into play on the centre/kingside with 22...Ra5!? or giving extra support to f6 by 22...Bd8.

23.h4?!

Ironically the engines now regard h4 as too slow, preferring to up the pressure on f6 with 23.Rf1, or down the g file with 23.Rhg1.

23...Bxd2?!

According to the engines it is better to break the pin on the f6 knight with 23...Qe6.

24.Nxd2 Ra5!?

Komodo12.1.1 likes this for a while but comes nearer to agreeing with Stockfish14.1's verdict that breaking the pin with ...Qe6 is much better.

25.h5?!

On the principle that "a threat is more powerful than its execution."

This may look strong but misses a detail. The engines reckon 25.Rf1 gives White a large advantage.

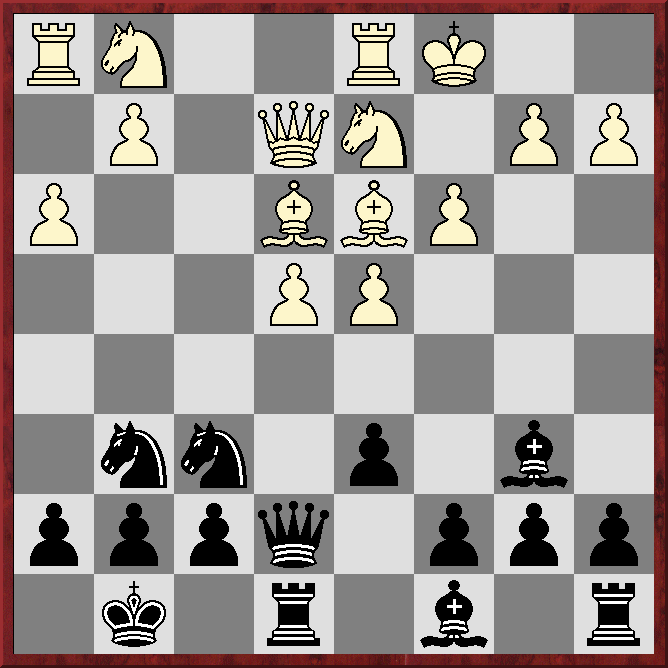

|

| Black to play and get a winning advantage |

*****

*****

*****

*****

*****

25...Rxg5!

Compulsory and compelling. This sacrifice of the exchange completely alters the picture.

Saving the g6 knight by 25...Nf8 runs into 26.Rhg1, while 25...Nf4 26.Bxf4 Nxg4 27.Qxg4 is very good for White, eg 27...f5 28.Qg6 (not 28.exf5?? Bxh1) fxe4 29.Bxd6 with Bc4 to come. After the text the game still has a long way to go, but Black is winning.

26.Rxg5 Nf4 27.Qf3 Nxd3 28.d5!?

If 28.Qxd3 [then] Nxe4 and wins. White, in trying to redress the balance, must continue his artificial evolutions.

28.Rhg1!? has been given in annotations as drawing after 28...Bxe4 29.Rxg7+ Kh8 30.Nxe4 Qxe4 31.Qxe4 Rxe4? 32.Rxf7 Nxh5 33.Rxb7, but the engines improve significantly with 31...Nxe4, eg 32.Rxf7 Nb4 33.Rc7 Rf8 etc.

28...Nxd5!?

A trenchant reply, eg 29.exd5 Qxg5 etc, or 29.Rxd5 Bxd5 30.exd5 Qe5 31.Nc4 Qc3 etc.

29.Rhg1

The sequel will show that White's threats amount to only one check. The crisis is near.

If 29.Qxd3 Black has several ways to win including 29...Qxg5, 29...Qf6!? and 29...Nc3+.

29...Nc3+ 30.Ka1

If 30.Kc2 [then] 30...Qxg5 31.Rxg5 Ne1+ and wins.

30...Bxe4 31.Rxg7+

If 31.Nxe4 Black wins with 31...Nxe4 32.Rxg7+ Kh8 33.Qf5 Nf6 (or, for example, 31...Qe5+), but not 31...Qxe4?? 32.Rxg7+ Kh8 33.Rh7+ (33.Rg8+ also wins) Kxh7 34.Qxf7+ Kh6 35.Qg7+ Kxh5 36.Qg5#.

31...Kh8 32.Qg3!?

Threatening mate in two by 33.Rg8+ or 33.Rh7+. If 32.Nxe4 [then] 32...Nxe4.

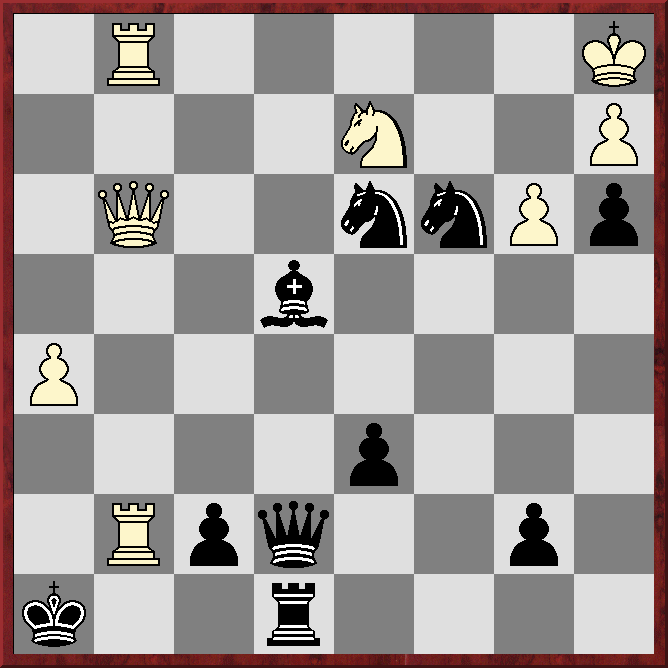

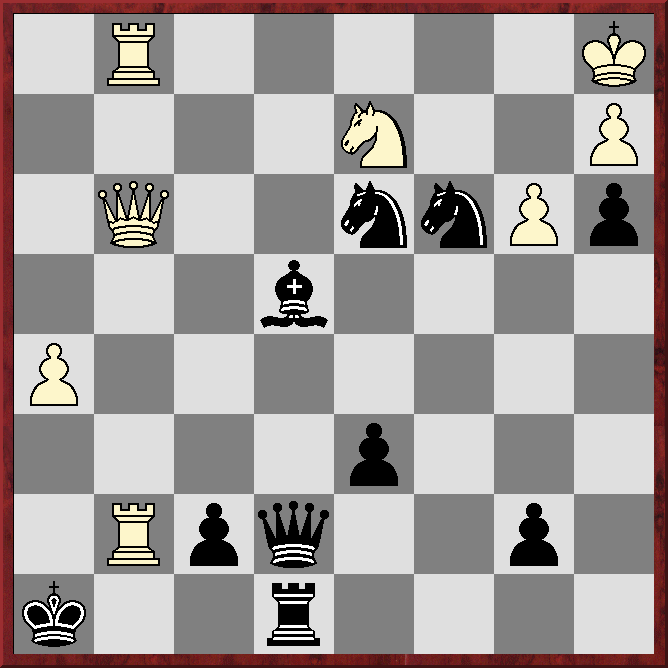

|

| Black to play and win |

*****

*****

*****

*****

*****

32...Bg6?

A manoeuvre with two objectives: closing White's base of action (the g file), and unmasking his own artillery.

The text loses, as does 32...Bg2? 33.Qxd3 Kxg7 34.Rxg2+ etc, but Black has a win with 32...Qf6 33.Rg8+ Kh7 34.Rg7+ Kh6.

33.hxg6 Qe1+

An original finish.

Black is mated after 33...Kxg7 34.gxf7+, but the text also loses.

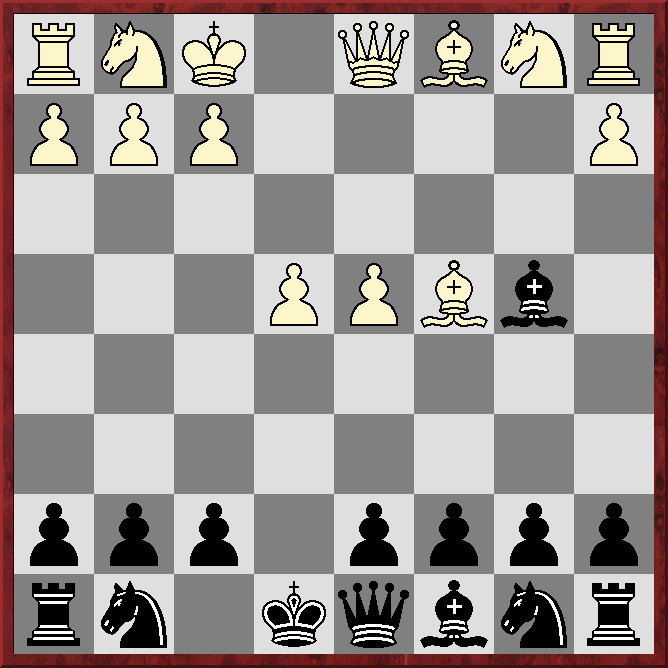

|

| White to play and win |

*****

*****

*****

*****

*****

34.Rxe1??

White wins with 34.Nb1 Qxg3 35.Rh7+ Kg8 36.gxf7+ Kxh7 37.Rh1+! Kg7 38.fxe8=Q etc, or 34...Kxg7 35.gxf7+ Qxg3 36.fxe8=N+! etc.

34...Rxe1+ 35.Qxe1 Nxe1 36.Rh7+

The Frenchman by now must have seen what was coming, but sportingly allows his opponent to play out the pretty finish.

36...Kg8 37.gxf7+ Kxh7 38.f8=Q Nc2#.